Nursing Workload in Critical Care | World Mental Health Day

By Paul Garvey*

Many nurses who leave the profession do so within the first three years of practice. The reasons for this are numerous and complex, but what is known is that all staff in the NHS are facing high workloads. A study I am planning to commence in the new year aims to develop a deeper understanding of how early career nurses manage their workload in critical care units, and the factors that influence their practice, experience, and perceptions.

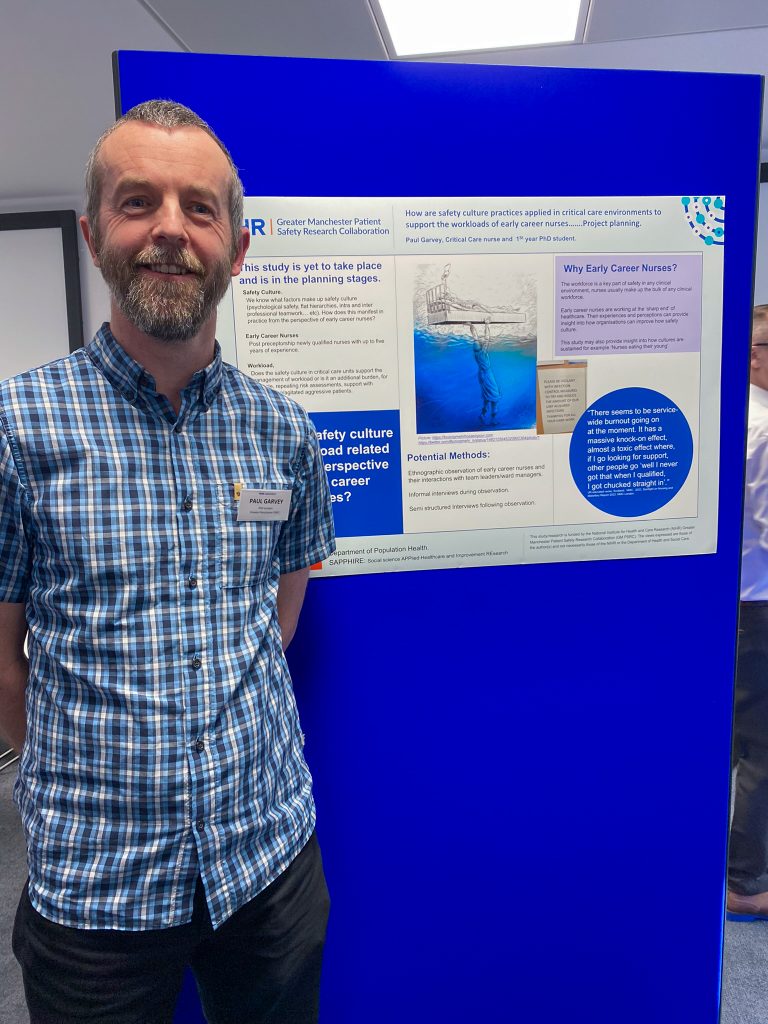

Paul Garvey presenting his PhD poster at the SafetyNet PhD Networking Event 2024

Prior to becoming a GM-PSRC-funded PhD candidate within SAPHIRE at the University of Leicester, I worked for 17 years as a critical care nurse in a variety of hospitals, always in patient-facing roles. It was a job that I loved, but it was also a job that had changed considerably over that time. When I first started, you would get into trouble if two fully equipped and staffed beds were not ready to be used at a moment’s notice. When I left, you would be lucky if there were two beds available anywhere in the hospital.

The work of healthcare providers has also evolved; patient needs are now far more complex, and people are living longer with multiple interrelated health problems. I would argue that staff workloads are far higher now than when I started. This is reflected in the increasing number of frontline staff experiencing poor mental health as they constantly try to juggle competing demands. The excellent work from Exeter University, as part of their Care Under Pressure theme, clearly highlights the detrimental impact of healthcare work on frontline staff. An NIHR themed review also highlighted that there is increasing evidence demonstrating that staff wellbeing is related to patient experience.

Staff strive to provide high-quality, patient-centred care, but the huge variety of work can make deciding what to prioritise difficult. This is especially challenging for staff at the start of their careers, who are still acquiring skills and experience. Complex machines like ventilators need to be monitored, and the often life-sustaining medications that patients require must be delivered without interruption. Patients need to be moved to prevent pressure sores and to help with their hygiene needs. There is also the often demanding but vital work of updating and supporting the friends and family of patients, who, like the patient, are also going through a significant life event.

Alongside all of this professional nursing work is the equally important bureaucratic work: ensuring that risk assessments are completed, discharge and admission paperwork is accurate, and chasing blood results or specialist teams. What would you prioritise? Would you deal with the hygiene needs, speak to and update the family, prepare some drugs for later on, complete the risk analysis, or have a cup of tea because you haven’t stopped yet in your third 12-hour shift this week? Staff often neglect their own self-care at work to ensure the needs of their patients are met, and they are often happy to do so in extreme circumstances. However, when this happens repeatedly, it can lead to a negative impact on the physical and mental health of those very people that patients are dependent on.

This study will collect data through semi-structured interviews with early career critical care nurses across the country and through non-participant observation of early career nurses in practice. This focus on nursing staff at the start of their careers ultimately seeks to identify ways for staff and organisations to develop interventions that support skill development in managing workloads, which can be embedded in early-career practice. This will inform safe, high-quality practice throughout nurses’ careers, reducing the detrimental effects on their health and well-being and improving outcomes for patients.

*This blog was written by Paul Garvey, a nurse and PhD Candidate at GM PSRC Enhancing cultures of safety theme, in reflection of World Mental Health Day.

Contact: PJG35@leicester.ac.uk

@IC_nurse

Suggested papers

This year’s World Mental Health Day theme is “Mental Health at Work.” Here are some suggested papers related to the mental health needs of healthcare professionals and the impact on patient safety:

- European Nurses’ Burnout before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on Patient Safety: A Scoping Review (mdpi.com)

- Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis | The BMJ

- The mental health needs of healthcare workers: When evidence does not guide policy. A comparative assessment of selected European countries – PubMed

- Association of strong opioids and antibiotics prescribing with GP burnout: a retrospective cross-sectional study | British Journal of General Practice (bjgp.org)

- How can we measure psychological safety in mental healthcare staff? Developing questionnaire items using a nominal groups technique | International Journal for Quality in Health Care | Oxford Academic

- Investigating the links between diagnostic uncertainty, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention in General Practitioners working in the United Kingdom – PMC (nih.gov)

- Exploring Associations between Stressors and Burnout in Trainee Doctors During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK – PubMed (nih.gov)

- Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis | Professional Well-being | JAMA Internal Medicine | JAMA Network

- Factors Associated With Burnout and Stress in Trainee Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis | Medical Education | JAMA Network Open | JAMA Network

Editorials:

- Time for a rebalance: psychological and emotional well-being in the healthcare workforce as the foundation for patient safety | BMJ Quality & Safety

- Editorial: The public health problem of burnout in health professionals – PMC (nih.gov)

- Tackling burnout in UK trainee doctors is vital for a sustainable, safe, high quality NHS | The BMJ

0 Comments